Debugging

The Call Stack

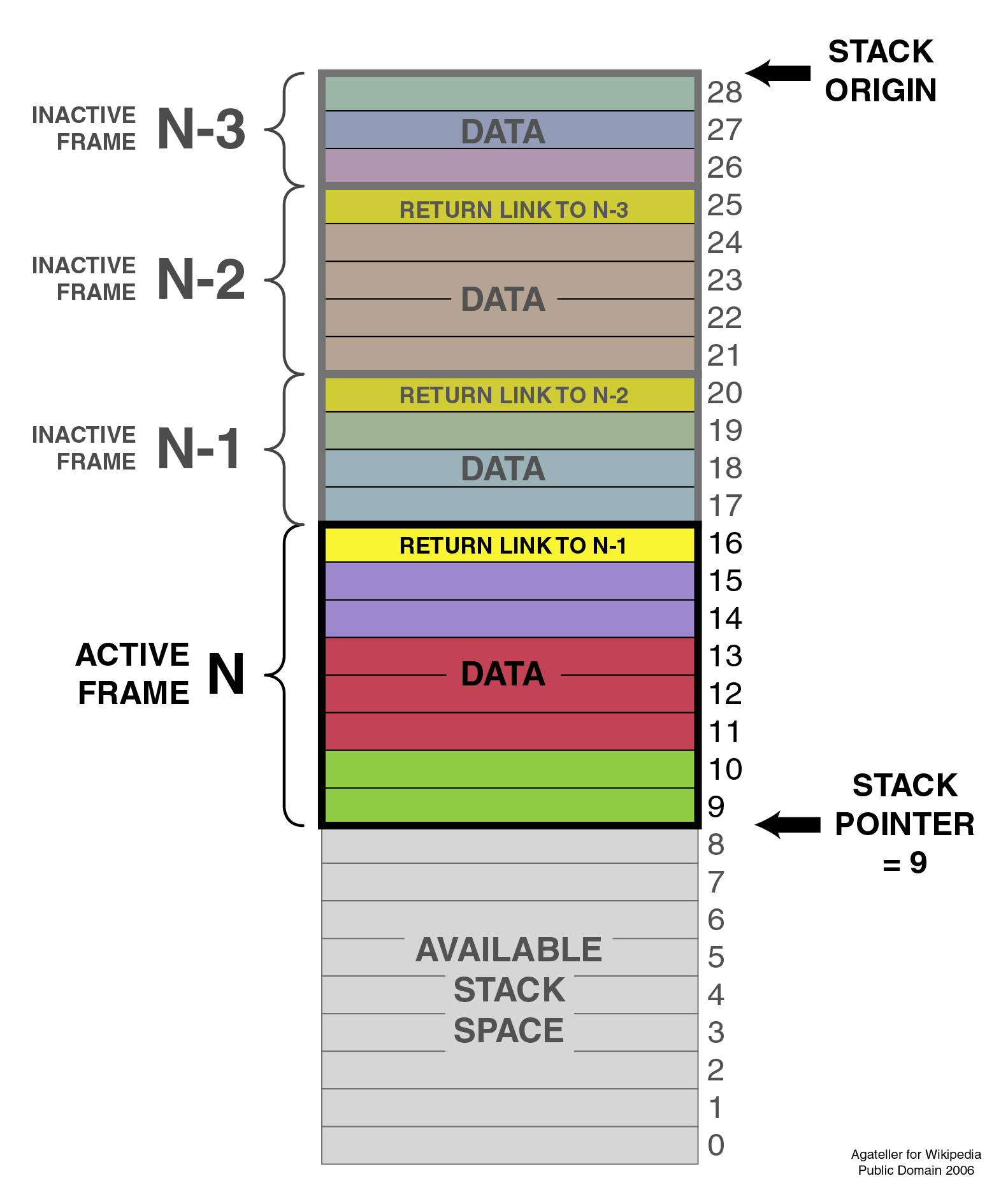

A stack is a Last-In-First-Out (LIFO) data structure, kind of like a stack of plates.

The call stack is a stack data structure that stores information about the current active function calls.

The objects in the stack are known as “stack frames”. Each frame contains the arguments passed to the function, space for local variables, and the return address.

It is usually (unintuitively) displayed like an upside-down stack of plates, with most recent frame on the bottom.

When a function is called, a stack frame is created for it and pushed onto the stack.

When a function returns, it is popped off the stack and control is passed to the next item in the stack. If the stack is empty, the program exits.

Visualize the Stack

How deep can that stack be? Let’s find out.

i = 0

def recurse():

global i

i += 1

print(i)

recurse()

recurse()

That maximum stack depth value can be changed with sys.setrecursionlimit(N).

See: https://docs.python.org/3/library/sys.html#sys.setrecursionlimit.

If we try to put more than sys.getrecursionlimit() frames on the stack, we get a RecursionError (derived from RuntimeError), which is Python’s version of the Java’s StackOverflowError.

import inspect

def recurse(limit):

local_variable = '.' * limit

print(limit, inspect.getargvalues(inspect.currentframe()))

if limit <= 0:

return

recurse(limit - 1)

return

recurse(3)

Exceptions

Ask forgiveness, not permission.

—Grace Hopper

When either the interpreter or your own code detects an error condition then an exception will be raised.

The exception will bubble up the call stack until it is handled. If it’s not handled anywhere in the stack, the interpreter will exit the program.

At each level in the stack, a handler can either:

Let it bubble through. This is the default if no handler is found.

Swallow the exception. This is the default for a handler.

Catch the exception and raise it again.

Catch the exception and raise a new one.

Handling Exceptions

The most basic form uses the built-ins try and except.

def temp_f_to_c(var):

try:

return(float(var) - 32)/1.8000

except ValueError as e:

print("The argument does not contain numbers\n", e)

finally, else, and raise

x = 5

y = "this"

try:

result = x / y

except (ZeroDivisionError, ValueError) as e:

print("caught division error or maybe a value error:\n", e)

except Exception as e:

# only catch "Exception" if absolutely necessary, or if planning to re-raise

errors = e.args

print(f"Error({errors})")

# or you can just print e

print("unhandled, unexpected exception:\n", e)

raise

else:

print("do this if there is code you want to run only if no exceptions, caught or not")

print("errors here will not be caught by above excepts")

finally:

print("this is executed no matter what")

print("this is only printed if there is no uncaught exception")

It is even possible to use a try block without the exception clause:

try:

5/0

finally:

print("did it work? why would you do this?"")

Built-in Exceptions

[name for name in dir(__builtin__) if "Error" in name]

If one of these meets your needs, by all means use it. You can add messages to them, too:

raise SyntaxError("That was a mispelling")

If no built-in exceptions work, define a new exception type by subclassing Exception.

class MyException(Exception):

pass

raise MyException("An exception doesn't always prove the rule!")

It is possible, but discouraged to catch all exceptions. Seriously, do not do this.

try:

my_cool_code()

except: # bad! do not do this!

print("no idea what the exceptions is, but I caught it")

An exception to this exception rule is when you are running a service that should not ever crash, like a web server. In this case, it is extremely important to have very good logging so that you have reports of exactly what happened and what exception would have been thrown. But it’s important to always catch at least the Exception exception.

try:

my_cool_code()

except Exception: # ok! this is safe but not recommended

print("no idea what the exceptions is, but I caught it")

Debugging

You will spend most of your time as a developer debugging.

You will spend more time than you expect on google.

Small, tested functions are easier to debug.

If you find a bug then make a test to prove that you fixed it and so that it doesn’t come back.

Tools

interpreter hints

print()

logging

assert()

tests

debuggers

The Stack Trace

You already know what it looks like. Here is a simple traceback:

$ python3 define.py python

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "define.py", line 15, in <module>

definition = Definitions.article(title)

File "/Users/maria/python/300/Py300/Examples/debugging/wikidef/definitions.py", line 7, in article

return Wikipedia.article(title)

File "/Users/maria/python/300/Py300/Examples/debugging/wikidef/api.py", line 26, in article

contents = json_response['parse']['text']['*']

TypeError: 'method' object is not subscriptable

But things can quickly get complicated. You may have already run into stacktraces that go on for a 50 lines or more.

Helpful Hints for Stacktraces

It may seem obvious, but read it carefully!

What is the error? Try reading it aloud.

The first place to look is the bottom.

Trace will show the line number and file of exception/calling functions.

More than likely the error is in your code, not established packages. - Look at lines in your code mentioned in the stacktrace first. - Sometimes that error was triggered by something else, and you need to look higher. (Probably more than one file in the stacktrace is your code.)

If that fails you:

Make sure the code you think is executing is really executing.

Simplify your code to the smallest code that causes bug.

Pull out a debugger, possibly from your IDE.

Save and

printintermediate results from long expressions.Try out bits of code at the command line.

If all else fails then write out an email that describes the problem:

Include the stacktrace.

Include steps you have taken to find the bug.

Include the relative function of your code.

Often, after writing out this email, you will realize what you forgot to check, and more often than not, this will happen just after you hit send. Good places to send these emails are other people on same project and mailing list for software package. For the purpose of this class, of course, copy it into Slack or the class email list.

Print

print("my_module.py: my_variable: ", my_variable)You can use print statements to make sure you are editing a file in the stack.

Console Debuggers

pdb/ipdb

GUI debuggers

IDEs: Eclipse, Wing IDE, PyCharm, Visual Studio Code

Use the Interpreter

Investigate import issues with -v. This will give you a very verbose output of everything being imported and more.

$ python -v myscript.py

Inspect environment after running script with -i. This will dump you into a Python REPL after the program exits so you can see what the environment looked like at the time of death.

$ python -i myscript.py

Other useful tools for debugging include:

If you are using IPython,

whowill list all currently defined variables.locals()globals()dir()

pdb - The Python Debugger

See: https://docs.python.org/3/library/pdb.html

Pros:

You have it already, ships with the standard library.

Works with any development environment.

Cons:

Steep-ish learning curve.

Easy to get lost in a deep stack.

Watching variables isn’t hard, but non-trivial.

The Four Ways of Invoking pdb

Postmortem mode

Run mode

Script mode

Trace mode

Note: in most cases where you see the word ‘pdb’ in the examples, you can replace it with ‘ipdb’. ipdb is the ipython enhanced version of pdb which is mostly compatible, and generally easier to work with. But it doesn’t ship with Python.

Postmortem Mode

This mode is For analyzing crashes due to uncaught exceptions.

$ python -i script.py

>>> import pdb; pdb.pm()

Run Mode

pdb.run("some.expression()"")

Script Mode

$ python -m pdb script.py

Trace Mode

Insert the following line into your code where you want execution to halt:

import pdb; pdb.set_trace()

It’s not always OK or possible to modify your code in order to debug it, but this is often the quickest way to begin inspecting state.

pdb in IPython

In [2]: pdb

Automatic pdb calling has been turned ON

%run app.py

# now halts execution on uncaught exception

If you forget to turn on pdb, the magic command %debug will activate the debugger in ‘post-mortem mode’.

Invoking pdb with pytest

pytest allows one to drop into the PDB prompt via a command line option:

pytest --pdb

This will invoke the Python debugger on every failure. Often you might only want to do this for the first failing test to understand a certain failure situation:

pytest -x --pdb # drop to PDB on first failure, then end test session

pytest --pdb --maxfail=3 # drop to PDB for first three failures

Try some debugging! Here is a fun tutorial intro to pdb that someone created: https://github.com/spiside/pdb-tutorial

Python IDEs

PyCharm

From JetBrains, this integrates some of their vast array of development tools. The free Community Edition (CE) is available. It has great visual debugging support.

Eclipse

A multi-language IDE with Python support.

It has automatic variable and expression watching and supports a lot of debugging features like conditional breakpoints, provided you look in the right places!

Visual Studio Code

This is not the same as Visual Studio. Visual Studio Code is a much smaller quasi-IDE that has support for Python.